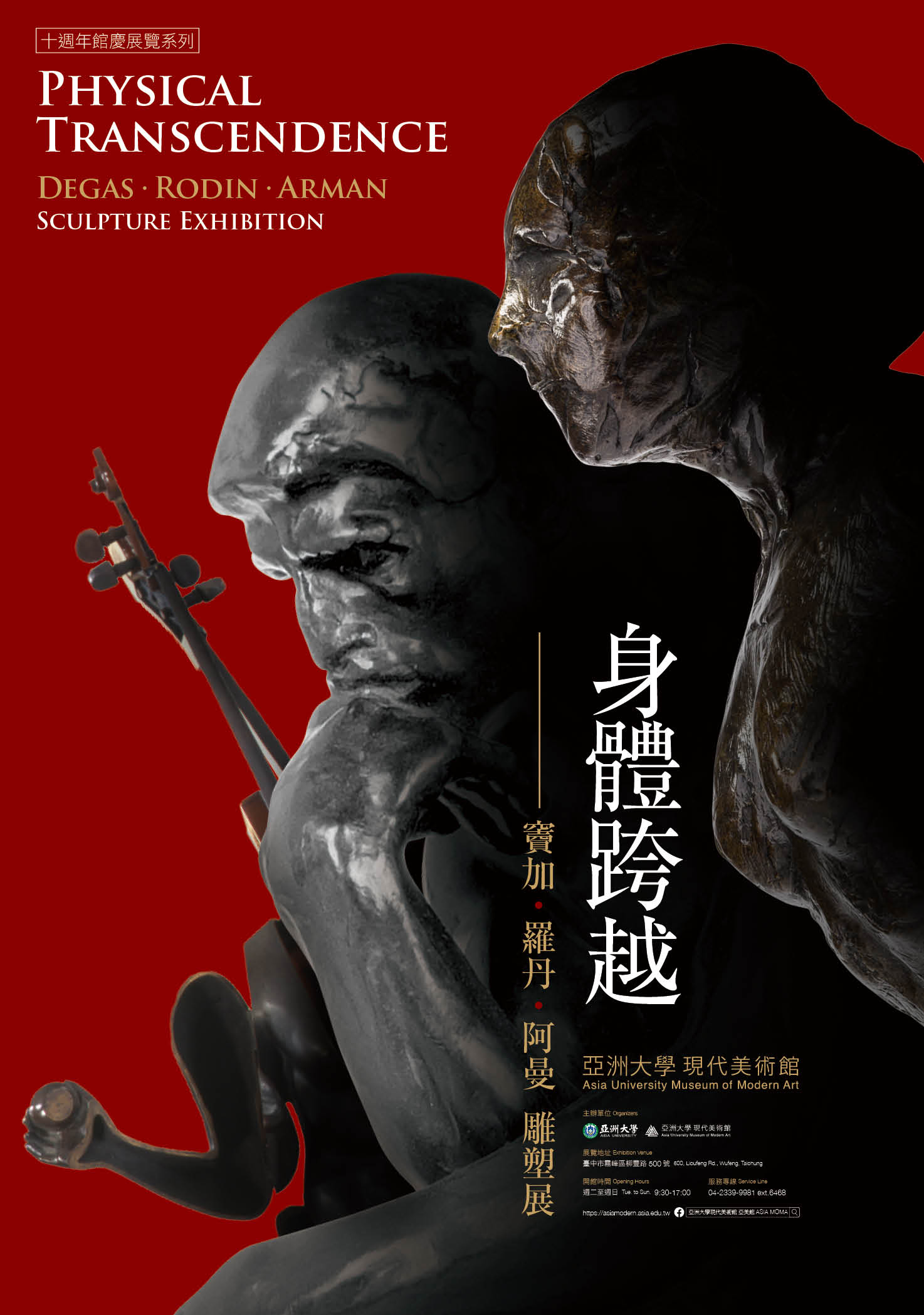

Physical Transcendence—Degas‧Rodin‧Arman Sculpture Exhibition

The sculptures in the western art history at first treated the Greek statues as the paradigm. In the mythology figures, historical stories, Olympic athletes, or the figures from the Greek tragedies, the presentation of wise bodies is created on the basis of ideal beauty. Such sense of body is oftentimes referred to as the presentation of the classical beauty. In comparison, this permanent collection exhibition displays the treasured collection of Asia University, encompassing the precious sculptures by Degas, Rodin, and Arman.

Edgar Degas

Degas was known for his painting before his death. The only sculpture ever exhibited was Litte Dancer displayed in the second impressionist art exhibition in 1881. Little Dancer was created in 1878-1881 with a full name Little Dancer, Aged Fourteen. The work was created after the Franco-Prussian War, as France gradually recovered from the defeat, and the impressionist had had multiple exhibitions. Degas was keen on the joint exhibitions of impressionists. He was only absent once. However, he did not get along with his peers, nor did he enjoy the ridicule and sarcasm against the impressionism. Nevertheless, the subject-matters and compositions of his works were deeply influenced by the impressionism, always intimately tied to the society in reality. Restaurants, streets, and the ballet classroom he was fond of, for example, were the places he drew his inspirations from.

Starting from the 1870s, Degas had been creating sculptures relentlessly. He began with observation of people in reality, producing a series of works of personal observation. Unfortunately, these works centering around on ballet practice were neve on display in his lifetime. They were merely produced as wax sculptures. After the death of Degas, his heir found 150 wax sculptures in his studio, with some of which severely damaged. After the consultation with a foundry, 74 of the works were cast into bronze sculptures, which are truly of rarity. The original works were debuted in 1881. Joris-Karl Huysmans (1848-1907), an eminent French art critic, commented at the sight of Little Dancer, “The terrible realism of this statuette makes the public distinctly uneasy: all its ideas about sculpture, about cold lifeless whiteness, about those memorable formulas copied again and again for centuries, are demolished. The fact is that on the first blow, M. Degas has knocked over the traditions of sculpture, just as he has for a long time been shaking up the conventions of painting. In taking up the method of the old Spanish masters, M. Degas has made it entirely unique, modern, by the originality of his talent. ” (Huysmans, L’Art moderne, 226-7.) The sculptures of Degas drew inspirations from his observation in real life, which are rich in mundanity. Little Dancer presents the fourth position of ballet, with her arms and hands taut at her back, one leg forward, and eyes closed, as if she is standing to regulate her breath, poised to dance. This position is at the most relaxing moment of body, prior to the onset of continual dancing. This is an epoch-making sculpture. Aside from the command of the captivating moment in the continual movement, Degas utilized real satin as the tutu for the model, and a real satin as the ribbon on the braids at the back of the statuette. It broke free from the conventional marble statue presentation. Mixing real-life objects with sculpture, he flipped the means of the traditional sculpture presentation. In addition to this work, Degas employed the stretching and movements of ballet dance body, or the body movements in life, exhibiting the mundane quality of body. Thanks to this movement, the human existence is thus transformed from the majestic formal beauty of sanctified classical mythology and monuments of great figures into the mundane beauty of body, returning from sanctity to human reality.

Auguste Rodin

Rodin has been known for his sculpture. He applied twice for, and rejected by, the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris, before he directed his attention to religion out of frustration. The sectarians were convinced that he was characterized by his talent in art, not suitable for the religious path. Therefore, he went to teachers again to study sculpture. Rodin traveled to Italy for study. Sauntering around Duran, Genoa, Pisa, Venice, Florence, Rome, and Naples, he uncovered the mysteries in the artistic practices of Donatello (1386-1466) and Michelangelo(1475-1564). The post-Baroque sculpture tradition in Europe inclined towards the formalist beauty. Despite the influence of neoclassicalism during the late 18th century to the early 19th century, the works of sculpture, while sustaining in essence the Renaissance legacy, evolved towards formalist presentation.

From the postures of sculptures, the ratio between the planed surface and the almost smooth surface, as well as the non finito (not finished) technique and aesthetics, Rodin discovered the mysteries of the Renaissance maestros. The Age of Bronze (L'Âge d'airain, 1877), the work he made his debut with, faithfully presents the flesh, the twisted body, and the vibrant spiritual essence. He abandoned the harmonious relationship born from the free leg, engaged foot, and hand-held object. The lad raises his both arms for stretch. Owing to its lifelike appearance, the artist even met with the controversy over whether it is modeled from a real person, which made him famous as well. The other work, Saint Jean Baptiste (1878), further employs a miner as the model. A hand is raised as if he is in sermon. Yet, his feet are firmly set on the ground, breaking free from the tradition of free leg and engaged leg since the Classical Greece. The former digested Donatello’s sense of body in the early Renaissance, with the subject being an anonymous youth, instead of a historical figure, nor of a mythological subject-matter. The latter entirely got rid of the classicist tradition since the Renaissance, presenting the temporal continuum of body, as opposed to the instant of a figure in the traditional sculpture. The Gates of Hell (La Porte de l'Enfer), commissioned by the government for the future Decorative Arts Museum, was inspired by Dante’s The Divine Comedy (La divina commedia) and Baudelaire’s The Flowers of Evil (Les Fleurs du Mal). The sculpture of seven meters tall and 8 tons heavy was never delivered, or cast into bronze, in Rodin’s lifetime. He kept working on it until the last moment of his life. After his decease, it was handed over to the foundry of Alexis Rudier, the predecessor of Musée Rodin, for casting in 1928. Adam, Eve, and The Thinker (Le Penseur) completed in 1882.

Leveraging light, tactility as well as the command in the details of body, figure’s movement, and the “non finito” approach, Rodin’s oeuvre exhibits a unique style. The figures evince powerful tension and inner energy from their difficult and novel movements. Eight of his works are on display in this exhibition, presenting vigorous body and athletic vitality that bestow the modern spirit upon sculpture.

Arman

The French American sculptor Arman (1928-2005), born Armand Pierre Fernandez, is a French American artist, painter, sculptor, and visual artist. He graduated from the École Nationale des Arts Décoratifs in Nice in 1946. Arman also learned judo at a police school in Nice, where he met Yves Klein and Claude Pascal. The three subsequently went on a hitch-hiking tour around Europe. The artist enrolled as a student at the École du Louvre for the studies in archeology and Asian art in 1949, taught judo at Madrid, Spain in 1951, and served in the military for the French campaign in the Indochinese Penisula in 1952. He observed the German Dadaist Kurt Hermann Eduard Karl Julius Schwitters in 1954 and developed his practices with cachets. From 1959 to 1962, Arman began to create Accumulations and Poubelles (French: the trash bins). The trash bins meant to collect the strewn refuse for refuse. In 1960, he filled the gallery Iris Clert with trash, titled Le Plein (The Full). Klein produced another work, Le Vide (The Void). The two form a contrast to each other. The distinguished French art critic, Pierre Restany, hailed Arman as one of the forerunners for Nouveau Réalisme (New Realism) that worked on an array of practices, involving creative fields and methods like painting, collage, accumulation, destruction, and assemblage. In 1961, Arman made his debut in the United States. He employed two methods, i.e. Coupes and Colères, as well as used objects with a strong identity, such as musical instruments like violin and saxophone, aside from classical bronze statues, to destroy and assemble these old objects. Arman usually made use of objects in everyday life for his works, including Greek statues, musical instruments, cars/motorcycles, furniture, painting tools, or clocks/watches. Through dissembling, cutting, and assembling, the artist brought the potential meanings of these objects to light while creating visual forms in variety. He was convinced that there is no object that is useless, and that old objects often contain humanistic messages more than the new counterparts.

Two works of Arman, Venus au Violoncelle bois (1990) and Victoire en Chantant, are on display at this exhibition. Both were cut and assembled, with the statues of Venus and the winged goddess of victory, respectively. After the destructive cutting of the traditional statues’ universal beauty of body, the classical beauty is converted into the modern visual form. The function and musical meaning of cello is transformed into a dynamic form. The formal beauty of Venus and the musicality of cello are fused together to manifest the new aesthetics with activity and inactivity as one.

At this special exhibition, the works of Degas in the late 19th century deconstruct the cold beauty of marble since the classicism for the first time through the mundane movements of bodies. The works of Rodan feature the inner spirit of majesty beyond the formal beauty of human body, re-presenting the humanistic value since the Renaissance; Arman, who was active for half of the 20th century, deconstructs the traditional visual beauty through cutting and assemblage, creates destruction of old ideology, and renders whole new visual beauty and meaning.